Youth Inc caught up with British educationalist and pop culture expert Sir Christopher Frayling at the India Design Forum in March to talk about the changing landscape of young people’s culture.

Q. As a cultural historian and a keen observer of pop culture, how has young people’s involvement in pop culture changed over the years?

I think there’s two things: one is it’s become much more multicultural. Pop culture is nourished from all sorts of different cultures. In the ’50s it was all American. Now, if you are in London, for example, it’s Caribbean, it’s Indian, it’s Chinese, it’s all these different cultures which are brought to London and then a melting pot of ideas comes out of it. So you get rap music, you get all these other things. I think that’s one big change. The other is that it’s somewhat divided into sort of corporate culture on the one hand and small-scale, individual, independent… I think it’s a real division between a push towards everything becoming corporate and techno. And the push from these big companies to make everything the same and the individuality… I think that’s the… we never had that in the ’50s because the record industry was much smaller. You could innovate much more easily. Now it’s incredible difficult to break into these big corporations, so you have to work out a way of keeping your independence and innovations. I think that’s it. That’s the big difference. It’s interesting that national institutions are taking account–I’ve just written a catalogue myself about David Bowie for an exhibition that opens next week at the V&A. Who would have thought that the Victoria & Albert Museum, this great national museum…David Bowie! And three months ago, I co-curated the exhibition on Hollywood costume. That’s changing… This idea of high and low is changing a lot. So the institutions of high are beginning to understand low. So I think that’s the third big change probably. And that’s great for your generation because you’d be able to get into museums. We couldn’t. They wouldn’t touch it.

Q. Was there any particular moment or instance when you thought pop culture positively impacted the youth?

Well, on me, I was in a rock band in 1964 to 1966 called The Tribe in Scotland and it was terrible, but never mind. Roll over Beethoven was our signature tune. And for me it was a rite of passage, it was almost as important as a university education. And you’re working with lots of other people in a band and creativity of the band…but more generally…gosh…you can’t. It is, you know, ever since the 1950s the teenager was invented, right, if you ask anybody from the 20s, or the 30s or the 40s of the 20th century, teenagers didn’t exist. You were a child, then you became a grown-up. And this idea of the middle period between the age of, I don’t know, 14 and 21, was really the invention of the consumer boom in the 1950s. So the big thing now is, you know, that age group is the crucible of popular culture. That’s where the energy is, that’s where the new things come from. And that’s something that’s happened in my lifetime. It’s really impossible to…when I was growing up in the ’50s, teenagers didn’t exist. You look at paintings of children in the last century or the century before, and then little grown-ups. They’re dressed like their parents in sailor suits, suits, dresses. Suddenly you’re allowed to be your own age. And that’s new. I’m quite jealous of your generation because you’ve got all these other opportunities. But you’ve got to fight the big corporations because there is this real tendency to make everything the same now and all over the world.

I was involved in an exhibition at the V&A on Bollywood posters. And what was so sad was this wonderful tradition of handmade, painted posters–and there was a man on the opening night of the exhibition, this man – he was very old, I think he was second generation of this skill – and they gave him a wall of the gallery. And he had a postcard of a Shashi Kapoor film and from a postcard, at sight, without any measurements, he did a full-sized poster on the wall. It was awe-inspiring. And my students, my graphic design students at the Royal College, because I was running the Royal College at the time, were unbelievably impressed by this. So they got him to come into the College the following day – “How the hell did you do that, you know?” And what was sad in the exhibition was the modern posters were all the same – air-brushed, ink jet-printed, computer images, part of a global campaign for a movie – so, you make a Sholay today, it would be the same poster all over the world. That’s sad. It’s gone. So you have to invent new things and everything, so that’s the…that’s my big theme… is for youth to find their own way without becoming a part of a huge machine and becoming the same as everybody else. You’ve got this great tradition.

I was involved in an exhibition at the V&A on Bollywood posters. And what was so sad was this wonderful tradition of handmade, painted posters–and there was a man on the opening night of the exhibition, this man – he was very old, I think he was second generation of this skill – and they gave him a wall of the gallery. And he had a postcard of a Shashi Kapoor film and from a postcard, at sight, without any measurements, he did a full-sized poster on the wall. It was awe-inspiring. And my students, my graphic design students at the Royal College, because I was running the Royal College at the time, were unbelievably impressed by this. So they got him to come into the College the following day – “How the hell did you do that, you know?” And what was sad in the exhibition was the modern posters were all the same – air-brushed, ink jet-printed, computer images, part of a global campaign for a movie – so, you make a Sholay today, it would be the same poster all over the world. That’s sad. It’s gone. So you have to invent new things and everything, so that’s the…that’s my big theme… is for youth to find their own way without becoming a part of a huge machine and becoming the same as everybody else. You’ve got this great tradition.

I’ll tell you this one thing coming out of this conference is you’ve got an amazing visual and cultural tradition in this country. And the key thing is to find a way of adapting that to the contemporary world instead of it all being about the heritage. I mean, like my Bollywood man – what a great–no one else could do that. No one in the world had that skill. You did. Unfortunately, it’s gone but there are many other things that–maybe it’ll come back.

Q. Do you find any difference between the youth of Britain and the youth of India?

I think our education, our art education system, allows the students to be more angry, more difficult, more Bolshevik, oppositional; whereas, I think your educational system is a little bit more hierarchical where you sit at the feet of the master and so on. And I think you can’t have a really lively art school unless the students are fighting the previous generation. The painter David Hockney, he once said to me, “The key thing when you’re teaching is that your teacher must have a very, very strong point of view and that the student must disagree with it completely.” So you get this collision, and out of that collision you find your own voice. What’s awful is if the teacher agrees with everything, you know, that’s great, we love it, you’re terrific. Because then there’s no kind of energy. So either the teacher mustn’t agree or they mustn’t be hierarchical. I do think your education system is a tiny bit conformist. I think your art schools of the future have got to be more of an avant-garde, more of a sense that students’ ideas are good. Give them–let them go, let them, you know, the student really express themselves. I don’t know if I’m right about that, but that is one difference, I think. On the other hand, youth culture in India is really interesting, actually. It’s very, very exciting. Your music, your dance, your video, graphic design, your [vigil?]–it’s very distinctive, actually. And here’s a thought: if the 20th century was the American century – so we all loved American design and American music – what if the 21st century is the Indian century? What happens then? Then everyone will look to India for its design inspiration, so you better be ready!

Q. You were the chairman of the Arts Council for four years and over the years, funding to the arts has decreased. Do you think this will negatively impact young people who have a passion for the arts?

There is a danger because what happens is when you get a recession, most art… I’ll go the British example… I guess 70% of the Art Council’s money is the big, national companies – The Royal Shakespeare Company, The Covent Garden Opera, The Symphony Orchestras – and the danger is when times get hard that you cut the new, young, less established companies and you leave the big national companies alone. That’s the danger. So the establishment gets left alone and the new generation, the new shoots that are coming through, the little company that hasn’t really established itself, you cut that. It’s easy to cut those companies because they haven’t got a very loud voice and they’re not really mature. That’s the danger. That’s a real danger. You have to nourish the old with the new all the time. You have to cut the national companies in the same way but you have to also allow new things to come through, so there is a real danger. If you don’t do that so that the next generation doesn’t get hurt, and then the establishment becomes really boring without this new generation coming in to nourish it. That’s your job – to nourish the mainstream.

Q. How then can the youth engage in the arts in spite of the cuts in the arts fund?

There’s two routes, really. One is to work in one of these national companies, work in a very junior capacity in one of these and work your way up. But the other one, which is much more fun, is to create a world around yourself. You create a world around yourself and it’s an exciting, interesting world, and you knock on the door and say, “I’ve got something really interesting to say,” whether it’s dance, music, visual art or whatever it is. So you’ve made a world and suddenly someone says, “Yeah, that should be on the landscape.” That’s the really exciting way in. Some people say, “Well, okay, I’ll work as a tea boy/tea girl in National Theatre and maybe one day I’ll be very successful.” But it’s much more interesting to be on the outside with a good–you’ve got to have a good idea, though. And you’ve got to have the self-confidence to develop it. And you mustn’t allow yourself to get disillusioned with difficulty. It requires a very thick skin, actually, to build an arts company, but some of the most exciting developments in the arts have come from individuals who are fresh out of college, creating a world around themselves and having the confidence to really go with it. That’s what I say you should do.

Q. Of all the celebrities you’ve met and interviewed, who has been the most intriguing and interesting?

I used to interview a lot of Hollywood people on television. Whenever they had a season of films on telly, I’d interview them. And I interviewed Doris Day. And what was interesting about Doris Day is that feminists have written about her as this role model – “strong woman!” So I thought, “This is gonna be amazing. I’m gonna meet this woman,” and she had no idea about that at all! She was very traditional. It was an example of how people writing about someone is completely different from the person. She was very sweet. She was very nice, but she had nothing whatsoever to do with feminism. And that interested me a lot, actually. She also loves animals, so it was the only interview I’ve ever done on television with bloody dogs wandering around my feet. I don’t recommend this. Somebody once said, “You should never act with children or animals.” And I had all these fluffy little animals attach themselves to my shoe when I was trying to interview Doris Day, but that was very interesting. She lives in Carmel in California which is a lovely place, where Clint Eastwood was the mayor. And that was exciting as well. I guess Doris was really the exciting one. Again, you always romanticise your own youth. I grew up in the ’50s when Que Sera Sera and all these songs by Doris Day were there, so it was incredible to meet this woman because when you see someone on the big screen, they’re a hundred foot high with the most beautiful teeth and the most beautiful eyes and you can’t imagine they’re human beings, actually. And then you meet them and it’s like meeting you. That’s it. They’re human beings like everybody else. So that’s nice as well. Now, I guess Doris Day–also, I don’t think she’s ever given a career interview to anybody else except for me. And I don’t know why. Well, I wrote to her on Royal College of Art-headed note paper. I think she thought she was getting a knighthood! And so she agreed. And she’s never agreed to anybody else. That was nice too. It was unique.

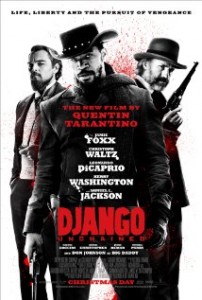

Q. Have you watched Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained? What did you think of it? Did you think his Oscar win was justified?

Q. Have you watched Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained? What did you think of it? Did you think his Oscar win was justified?

I have! I thought, “He’s stolen my record collection!” [laughs]. I loved the first half with the relationship between Django and the German bounty hunter. He absolutely got this atmosphere of gallows humour with brutality which the Spaghettis were so good at. I thought the second half, when it arrived at the plantation and got a bit heavy-going…you know, I’ve never seen an Italian Western where they talk too much [laughs]. And they talked too much in the second half, I thought. It, also like a lot of movies, was 20 minutes too long. These days films are so expensive. They always have to do two-and-a-quarter-hours. And 90 minutes was enough for the Spaghettis. But I thought the first half was fantastic and I loved the way he used the original music…okay, they commissioned a little bit of new music, but when I heard the theme, I hadn’t heard it since about 1966. It was – “You’ve stolen my records!” It was incredible. Now I enjoyed that. And I loved the way that…when I started studying the Italian Western, of course, nobody took it seriously. They thought I was completely mad. All the critics were saying that they were terrible movies, they copy American movies – just like they say about Bollywood – copy musicals or Sholay being a copy of some movie, you know. But now, it’s mainstream. Oscar nomination for a Spaghetti Western! Jesus! The world’s caught up.

Q. Do you think it was justified?

Yeah, I do. I thought it had real guts to it, actually. It wasn’t a great piece of art, but some evenings you don’t want to see a great piece of art. Actually, I think The Life of Pi should have won for Best Film. I really do. I thought that was the most incredible technical achievement. And I gather that everyone was worried in India that the tiger might have been maltreated, making it do the thing–it was 60% computer generated, so basically, a tiger sat there, on the ramp and the rest was drawings done fantastically. I couldn’t see the drawing. When the computers began and they, you know, I thought, technically, it was the one time that 3D for me – in the cinemas it was in 3D – really worked. You’re trapped on this boat and you’ve got this vanishing point on the boat and you’ve got to feel claustrophobic on this boat, just you and the tiger. And 3D really got this atmosphere of claustrophobia. It’s the first film I’ve ever seen where the 3D really worked, I thought. Never mind. But Django got in there as well, actually.