It was just over a year ago that a veiled Talib entered a school bus in Pakistan with a gun and questioned, “Who is Malala?” And now, responding to that question that changed her life, she says, “I am Malala.”

It was just over a year ago that a veiled Talib entered a school bus in Pakistan with a gun and questioned, “Who is Malala?” And now, responding to that question that changed her life, she says, “I am Malala.”

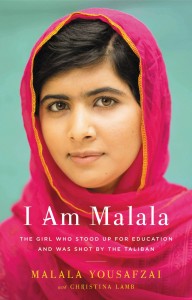

I am Malala is a chronicle of Malala Yousafzai’s journey from a simple schoolgirl in Swat Valley to a Nobel Peace Prize nominee. Assisted by British journalist Christina Lamb, a correspondent of Pakistani events since 1987, Malala tells her story. She was born to Ziauddin Yousafzai, a poor son of an imam in Swat, a Pashtun whose ancestors migrated from Afghanistan to Pakistan. Ziauddin’s life is a mirror to Malala’s own, as she reveals that getting an education was a battle for Ziauddin himself owing to his poverty. Ziauddin’s cherished dream was to start a school for children, a dream that needed to jump the many hurdles of insufficient funds, lack of supporters, scarcity of facilities and little interest from people in enrolling their children. But this dream did come to fruition and by the time Malala was born, Ziauddin’s school was functioning and was where Malala herself studied.

On the surface, Malala is like any other teenage girl. In her biography, she admits to enjoying the TV show Ugly Betty and the Twilight series of books. “It seemed to us that the Taliban arrived in the night just like vampires,” she writes. “They appeared in groups, armed with knives and Kalashnikovs… These were strange-looking men with long straggly hair and beards and camouflage vests over their shalwar kamiz, which they wore with the trousers well above the ankle. They had jogging shoes or cheap plastic sandals on their feet, and sometimes stockings over their heads with holes for their eyes, and they blew their noses dirtily into the ends of their turbans.”

The Taliban arrived with the promise of improving conditions in Swat Valley. Pakistan is fraught with issues related to negligence and religious complications. Malala writes with regret how the country’s government and army ignore Swat Valley for the most part. When devastating floods hit Swat in 2010, Pakistan’s then President Asif Ali Zardari was holidaying in France. “‘I am confused, Aba,’ I told my father. ‘What’s stopping each and every politician from doing good things? Why would they not want our people to be safe, to have food and electricity?’” At such times local Islamic groups provided assistance to the victims. And it was at such a time, when grievances against the established regime were many and faith in the system was shaky, that the Taliban, headed by a man called Maulana Fazlullah, arrived.

The courts in Pakistan are infamous for tarrying on cases for years, sometimes generations (not unlike our Indian courts). The Taliban established their own courts which promised to dispense quick justice in the name of Islam. While this won favour with the Swatis in the beginning, it became apparent that the Taliban was extremist and sought control. Swat was soon governed by the power of guns and bombs. People were publically flogged and slaughtered, and schools were shut down and bombed. It was a few years before the Pakistan army was sent to the Valley to rid the region of the Taliban. By then, the people of Swat had suffered much violence and oppression.

When the United States declared war on terror, it began sending drones to the Afghanistan-Pakistan region. These drones drop bombs on those places that terrorists were believed to be hiding. However, numerous independent reports have revealed that the largest casualties of the drone strikes are in fact innocent civilians. The anti-American sentiment is thus so strong in the region that Malala writes, “Where once we used to blame our old enemy India for everything, now it was the US.”

Malala’s home is a place entangled in this turmoil. She says that more than anything, her ardent wish is to go to school and live a normal life. Her courage and fortitude is obvious in the pages; she mentions how she and her friends went to school each morning, hiding their books and bags under their shawls and sneaking in to their school through the rear entrance. She also makes it clear that if it weren’t for her father, who encouraged her to be her own person and speak out against injustices, she wouldn’t be who she is today. Ziauddin made Malala a public figure, first by allowing her to blog in Urdu about life under the Taliban (under the pseudonym Gul Makai) and then taking her with him to his protest rallies and several television interviews where she spoke out against the Taliban.

Malala is a girl of extraordinary courage and immense fortitude, there is no doubt about this. Her biography is a gripping, sometimes horrifying-sometimes uplifting account of a girl fighting for equality. Her voice in the book, however, at many instances seems compromised. When Malala talks of the Pakistan government, its relations with the United States and even provides information on events unfolding far from the Swat, it seems that Christina Lamb is writing those words. The kind of confidence and information in those lines are more likely to spring from a journalist, not a teenage girl, and at such times the book feels like a betrayal because it is not an entirely faithful representation of Malala’s voice. One could reason that it is necessary to know these details as they put Malala’s experiences in context.

Ultimately, the goal of reading this book should be to sensitise one to the struggles of a people and the far-reaching consequences of their suppression. Read it for equality. Read it for liberty. Read it for all the Malalas who are fighting for a place in the world, the Taliban notwithstanding.

– Aparna Sundaresan